Por Camilo Rodríguez

No queremos desaprovechar este Mes de la Hispanidad para poner sobre la mesa unas lecturas de otoño que recuerdan y celebran nuestra cultura, nuestra historia y esta forma tan particular que tenemos de ver el mundo y de vivir en él.

Si les interesa descubrir o re descubrir lo hispano y lo latino, no dejen de acercarse a estos libros que tienen al alcance de unos clics.

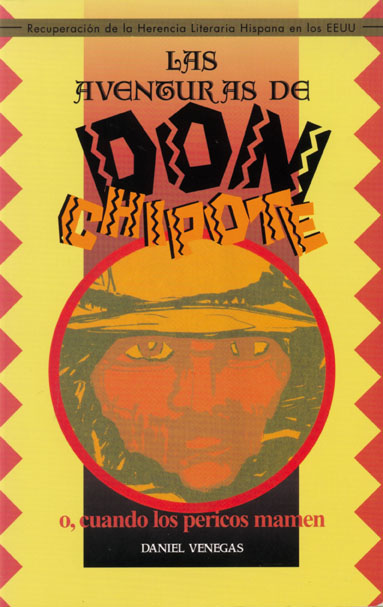

Las Aventuras de Don Chipote, (1999, Arte Público Press) Daniel Venegas

Esta, mis amigxs, es la primera novela chicana de toda la historia. Así como lo leen. LA PRIMERA. ¿Que qué? Pues verán, resulta que por allá por los años veinte del siglo pasado el periodista y editor autodidacta Daniel Venegas, quien ya tenía un diario llamado El Malcriado, decidió escribir un libro para la clase obrera chicana. ¿Y por qué? Pues bien, si la lengua castellana tiene al Ingenioso Hidalgo Don Quijote de la Mancha, a la lengua chicana le hacía falta un héroe fundador, un disparatado caballero que supiera lo que es trabajar en el traque, comprar comida en el “suplai” y que, aparte de la historia del migrante hispano, también conociera el anecdotario popular, el acervo, la lengua y el encanto mexicoamericano.

Y la verdad es que en nada desmerece Don Chipote a don Quijote de la Mancha, no le falta ni bondad ni valentía, ni su noble corcel que es el can Sufrelhambre. Tampoco su Sancho Panza, que se llama Policarpo y mucho menos su Dulcinea, la envolvente Pelona. De hecho, hasta su Penélope tiene nuestro héroe, cual Ulises en la Odisea, y esa es la buena y picante Doña Chipota, quien espera desde la dulce patria de México noticias de su amado, y le enviará misivas a su buzón en Peach Spring, sección siete.

De este libro, mis amiguis, obtendrán risas, aventuras y una clase magistral del argot chicano con el estilo clásico y joco-serio que caracteriza a Venegas. Aquí no se habla, se le da vuelo a la sin-hueso; aquí no se trabaja, se camella; aquí no se arma un cigarro, se tuerce uno de fajero. Y si buscan más, lo único que deben hacer es abrir este gozoso buc.

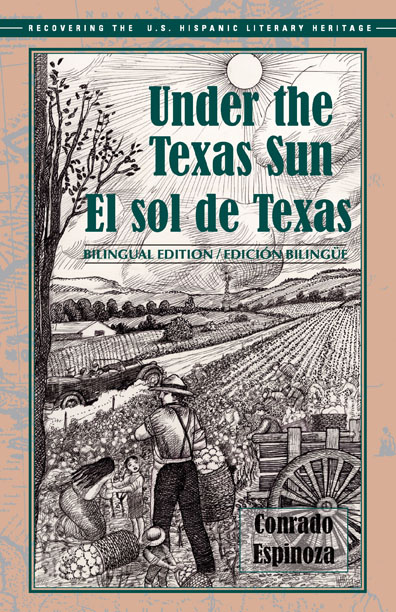

El sol de Texas (2007, Arte Público Press) Conrado Espinosa

Pero si lo tuyo es el drama o la historia, lo más atinado sería este novelón. ¿Te has preguntado quién vivía en Texas en los años 20? ¿Te interesa seguir la historia de los García y los Quijano, dos familias que lo dejaron todo hace más de un siglo y se vinieron a probar suerte en la tierra de las oportunidades? ¿Sabes cómo subsistían los primeros migrantes en las plantaciones de algodón, en las refinerías de petróleo y en la construcción ferroviaria en ese entonces? Este relato no solo responde a todas esas preguntas, sino que, por si fuera poco, es la primera novela de la literatura acerca de la inmigración mexicana y trae su respectiva traducción al inglés.

Los integrantes de las familias protagonistas encarnan la vida de muchos y muchas que hicieron lo posible para ahorrar el dinero suficiente y volver a su país natal a comprar su propia tierra. Sin embargo, las cosas no salen siempre como ellos quieren y El sol de Texas retrata esa desilusión.

Y ahora, para que no les falten las ganas de leerlo, les dejo a manera de abrebocas la cereza del pastel, el pilón; el fascinante inicio:

Acababan de cruzar el puente hacia los Estados Unidos. Sus pies estaban ahora firmemente plantados en el suelo que era su tierra prometida. Lo habían conseguido. ¡Bendita sea la Virgen de Guadalupe! Ahora no tenían que temer a los villistas, a los carrancistas, al gobierno o a los revolucionarios. Aquí podían encontrar paz, trabajo, riqueza y felicidad”. Así comienza la historia de la familia García, que como muchos de sus compatriotas, huyó de su patria durante la agitación de la Revolución Mexicana en busca de una vida mejor en los Estados Unidos. (Espinoza)

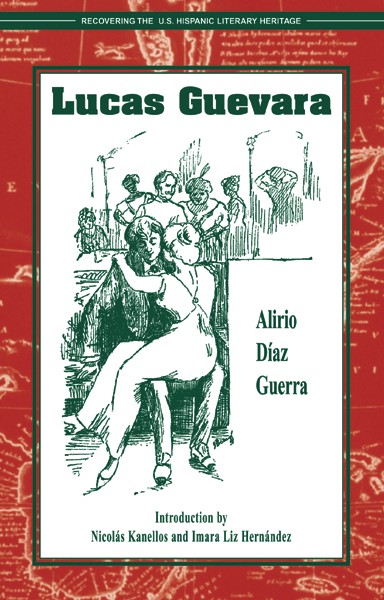

Lucas Guevara (2001, Arte Público Press) Alirio Díaz Guerra

Y nada mejor para terminar, mis cómplices lectorxs, que una novela con un escenario citadino. Y no cualquiera, sino acaso la primera novela urbana en español que se publicó sobre la inmigración norteamericana por allá en 1914.

Así es, Lucas Guevara nos invita a adentrarnos en la historia de un ingenuo joven, proveniente de un pueblito perdido en el campo sudamericano, que se enfrenta a ese monstruo de mil cabezas que es la metrópolis moderna con sus rascacielos, sus multitudes afanosas y el lado oscuro del Sueño Americano.

Al contrario de lo que pensaba, el joven Lucas no encuentra la calle pavimentada de oro ni el camino de la prosperidad, sino un mundo en donde todo se trata de comer o ser comido, y se deja seducir por los placeres carnales que encuentra en la vida nocturna de Nueva York.

Si sabes, o quieres saber cómo era la vida en las pensiones de la capital del mundo en un momento en que casi la mitad de sus habitantes eran inmigrantes, te hago un favor invitándote a leer este deslumbrante relato.

Y creo que con esto, mis amiguis, no les hace falta nada para llenar sus días de otoño con fascinantes historias que nos emocionan y nos recuerdan las luchas de la comunidad hispana en este suelo.

Camilo Rodríguez es doctorante de escritura creativa de la Universidad de Houston. Sus cuentos, crónicas y ensayos se han publicados en revistas y medios culturales como Revista Nexos (México), Revista Arcadia (Colombia) y Almíar (España). Sus intereses académicos incluyen el conflicto armado, la narrativa de viaje y la literatura de inmigración.